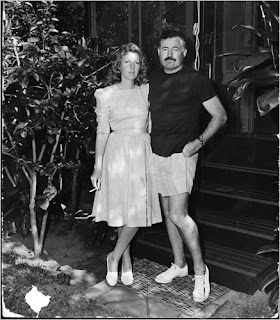

Hemingway and Gellhorn

I spent my morning in bed with a lusty man’s man. Hemingway again. No, I did not read For Whom The Bell Tolls again; I watched Hemingway and Gellhorn, a film about the love affair between writers Ernest Hemingway and Martha Gellhorn. He was a tortured artist, she an ambitious world-weary journalist. It was not a match made in Heaven.

Their love affair began as so many passionate, disastrous unions of the minds (and/or bodies) begin: in a bar. Hemingway was married but in possession of a wandering eye – an eye that focused on a young wandering journalist. They meet in a seedy moonshine shanty called Sloppy Joe's. She saunters over to the bar, where Hem is celebrating. The two exchange sharply pointed banter.

Their love affair began as so many passionate, disastrous unions of the minds (and/or bodies) begin: in a bar. Hemingway was married but in possession of a wandering eye – an eye that focused on a young wandering journalist. They meet in a seedy moonshine shanty called Sloppy Joe's. She saunters over to the bar, where Hem is celebrating. The two exchange sharply pointed banter.One gets the sense that Martha, played by Nicole Kidman, was a sincere person, earnest about her career, her ambitions, her passions. Hemingway, portrayed by Clive Owen, comes off like a showman, a charmer, more dedicated to his own pleasures and ego than any real cause.

When he utters, "The best way to find out if you can trust somebody is to trust them," you want to warn Gellhorn. "No, don't do it!"

And yet, despite the bellicose monologues, the pathetic drinking binges, the manic writing sessions, you are drawn to Hem. His magnetic fervor, his passionate pursuit of hedonistic pleasures, his commitment to his craft, make him seem larger than life and, admittedly, attractive. I could not help but think of Hem as a sexual being. I wondered if he brought his prodigious energies and passions to the bedroom.

Philip Kaufman, the man who directed Hemingway and Gellhorn, obviously spent time thinking about Hem's sexual prowess.

About 32 minutes into the film, Kidman and Owen tumble into bed. Outside the hotel room, the Spanish Civil War rages, bombs detonate; inside, the battle is staged on a primal level. Hem seduces Gellhorn with the finesse of a bull, charging forward, beautifully brutal, awesome in his masculinity.

As I watched these two strong, creative people come together, one yielding to the other, I knew the memory of that pairing was one of those singular events that remained with them throughout their lives. I imagined a gray-haired Gellhorn, gasping and pressing a wrinkled hand to her chest as she suddenly recalled that one, viscerally powerful night spent with a man she once loved.

One of the most powerful moments in the film, however, is when Hemingway's wife, Pauline, discovers he is having an affair with Gellhorn. The buttoned-down Pauline has an epic meltdown and screams, "She will leave you a broken man.”

Poor misguided Pauline. Gellhorn was not capable of breaking Hemingway, for he already was a broken, reckless, self-destructive man. Perhaps he was born that way, broken. But by adulthood he was well and truly shattered. In the film, Hemingway stands impassively watching his betrayed wife act out her pain – as cold and remote as the stuffed animal carcasses on his wall.

Sadly, he would not love or cherish Gellhorn anymore than he loved Pauline. He was not capable of loving, nor was Gellhorn, either, really. They were two broken, jagged pieces that did not fit together. Though they tried. They surely tried.

Something happens about two hours into the movie, some imperceptible shift occurs and we are permitted a peek through the thick, abrasive curtain shrouding the heart of Hemingway. Suddenly, I saw him through Gellhorn’s eyes, a brusque man with a quiet, powerful but limited capacity to love. He's the sort of man who appeals to women, strong, silent, scarred. They arouse in us a powerful desire to elicit words, love, healing. But their scars are too deep.

Hemingway and Gellhorn are sitting in a cave in China, having just been abandoned by a squad of soldiers. They are supposed to be on their honeymoon, but the ambitious Gellhorn wanted to pursue a story about resistance fighters in China, and so Hem grudgingly relented. Gellhorn/Kidman looks at Hem/Owen and realizes the sacrifice he has made in following her to war-torn, disease-infested China. She is about to thank him when he makes some obnoxious comment. The tension dissipates, the two laugh, and a beautiful, fleeting moment of pure love is captured.

A few minutes more and tone of the film changes shifts again and the curtain closes. Hemingway is back to being an angry, pontificating, self-absorbed bully. We see a shattered Hemingway, undergoing electroshock therapy and then putting the barrel of a gun into his mouth.

In that gripping cinematic moment, I loved Hemingway. I loved him for his brilliance, his charm, his vulnerabilities. I hated him, too. I hated him for being the embodiment of tortured genius. I hated him for not taking Gellhorn in his arms and never letting her go.

The thing is, even though these tortured souls were an unhealthy pairing, I can't help but wish they’d stayed together, the fuel of their passion would have been enough to keep their train on the track.

The movie ends with a cantankerous, hard-bitten elderly Gellhorn throwing reporters out of her home after they ask her about her brief marriage to Hemingway. She grumbles, "I am not a footnote to someone else's life!" Her snappishness left me wondering if she ever really loved Hemingway, or if the unsavory details of their affair had left her bitter.

The reporters leave and Gellorn slowly walks across the room to her desk, takes a seat and retrieves a weathered letter from a drawer. The letter is a love note from Hemingway, penned at the the height of their romance.

"My Dearest Marty, one thing you must know, love is infinitely more powerful than hate."

I felt my breath catch in my throat. Gellhorn did love Hemingway, went on loving him even though they could not be together.

Some loves are like that, aren't they? Flawed, but still powerful and true.

**I am not an expert on Hemingway or his works. The thoughts shared in this posting were formed while watching the HBO film Hemingway and Gellhorn.

Comments

Nancy

Thank you for your comment. I was never a fan of Hemingway, until a friend, someone I admire, recommended I study his prose. Now, I appreciate the simplicity and truth of his words. A Moveable Feast is my favorite.

All the best,

Leah